Category: Frontiers

-

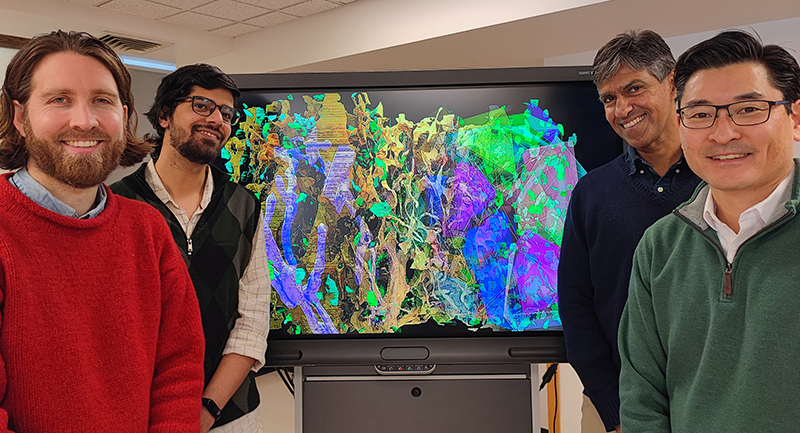

RI-MUHC and McGill researchers make a breakthrough in understanding brain nanoarchitecture, using computer vision

A new study published in Current Biology reveals the nanostructure of brain cells at an unprecedented level of resolution SOURCE: RI-MUHC. Brain cells are among the most anatomically complex cells in the human body. They create an intricate web of connections that enables the brain to detect, process, encode and respond to diverse information. Importantly,…

-

Krembil Brain Institute Scientist Carmela Tartaglia is finding ways to diagnose Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy before its too late

Traumatic brain injuries are considered to be an invisible condition. We can’t often see the effects and 50% of patients experience personality change, irritability, anxiety, and depression after concussion. Repeat traumatic brain injuries may increase your risk for a condition called Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Dr. Carmela Tartaglia’s research looks to identify diagnostic tools to predict…

-

Saving more stroke patients

Approximately 20,000 Quebecers suffer a cerebrovascular accident every year. Nearly 90% are caused by a blood clot that blocks the brain’s blood vessels and, by the same token, its supply of oxygen and nutrients. Deprived of oxygen, some 1.9 million nerve cells die every minute following a stroke. While no treatment can restore brain function, there is…

-

Exoskeleton robot helps researchers shed new light on learning and stroke recovery

UCalgary clinical trial maps how we learn motor skills, and the results could be a game-changer for stroke rehabilitation. This morning, you probably reached out of bed to turn off your alarm clock, and later brushed your teeth or buttoned a shirt. Those movements are routine; mundane, even. You are long past the point of…

-

Discovery reveals blocking inflammation may lead to chronic pain

Findings may lead to reconsideration of how we treat acute pain Using anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids to relieve pain could increase the chances of developing chronic pain, according to researchers from McGill University and colleagues in Italy. Their research puts into question conventional practices used to alleviate pain. Normal recovery from a painful injury involves…

-

CIHR Health Research in Action: Better sleep may lead to a better fight against Alzheimer’s disease

Research team at Université de Montréal offers insights that may help both detect and treat the disease among patients in the future Issue More than 750,000 Canadians are living with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). This complex neurodegenerative condition destroys brain cells and causes a gradual deterioration of memory and thinking. Research A key feature of AD…

-

Researcher and inventor Stephen Scott, from Queen’s University explores the impact of his robot, Kinarm, which is changing the way we understand the brain

In a research 5 à 7 presented by Queen’s University, Dr. Stephen Scott, Professor and Incoming Vice Dean Research for Queen’s Health Sciences, presents his invention: Kinarm. Trained in systems designs engineering, and with a background in physiology, Dr. Scott has combined two areas of expertise into something incredible. Kinarm is used to assess neurological…

-

Promising new treatment for ALS goes to clinical trials

After 12 years of research, Dr. Richard Robitaille is hopeful that we’ll soon have a treatment to help people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) regain mobility. A new clinical trial is set to start soon, thanks to a $1-million grant from the American ALS Association announced just before Christmas. “I’m still in shock! For me,…

-

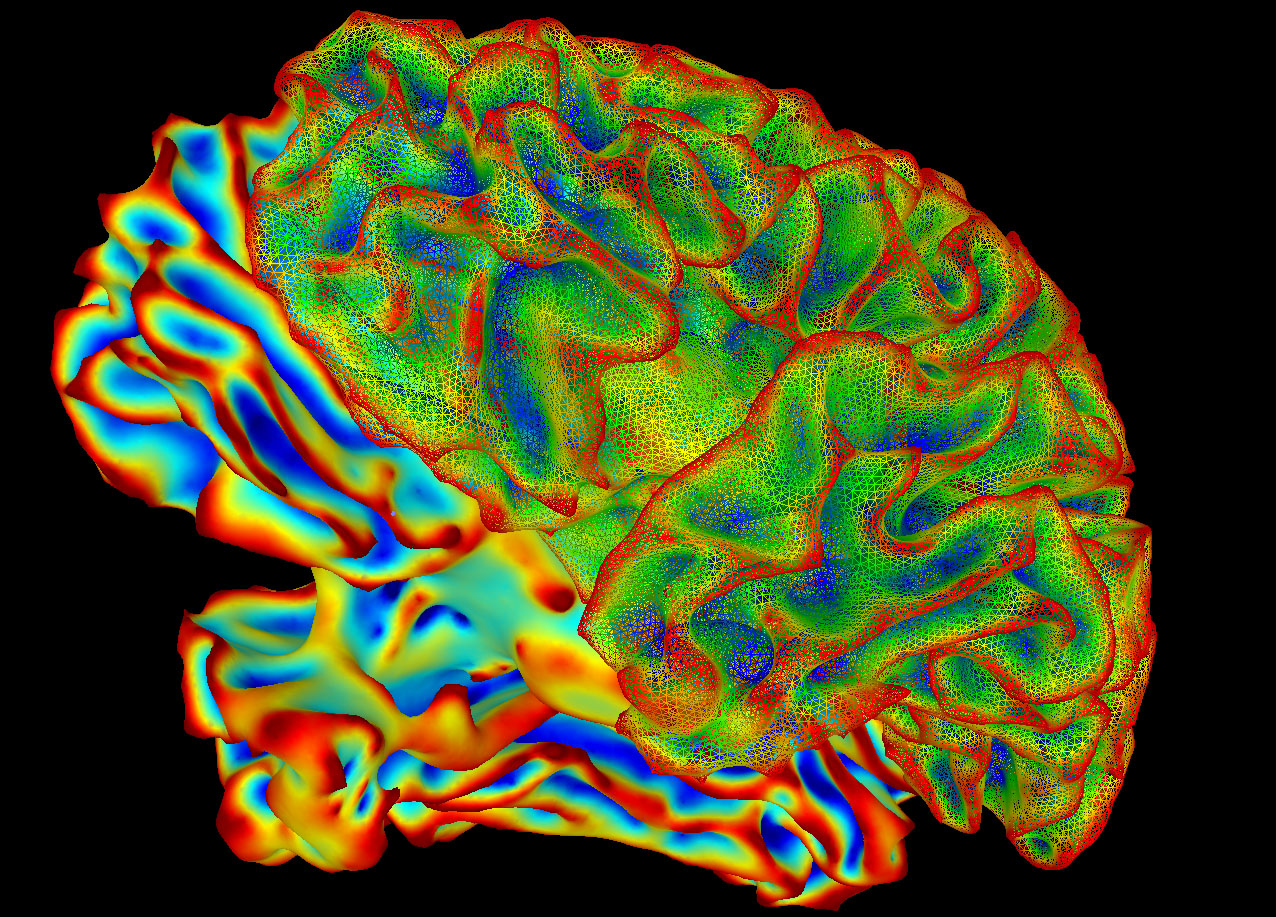

UCalgary researchers use computer modelling to simulate impact of Alzheimer’s on the brain

New way to model neural disease could lead to better understanding Author: Shea Coburn, Hotchkiss Brain Institute A deep neural network is a computerized brain-inspired machine learning model, which uses many layers of simulated neurons to mimic the function of the cerebral cortex. Each layer in the network creates more complex activity, which simulates the…

-

U of T research linking music to brain function could lead to promising therapies: CNN

A University of Toronto and Unity Health Toronto study found that listening to songs with special meaning for the listener improves brain function in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment, CNN reported. Senior author Michael Thaut, director of U of T’s Music and Health Science Research Collaboratory and a professor in the Faculty of…